Understanding economic moats is essential for investors looking to identify companies with long-term competitive advantages that can sustain profitability over time.

The term “economic moat” was popularized by Warren Buffett, the legendary investor and CEO of Berkshire Hathaway. Buffett used the metaphor of a moat to describe a business’s ability to defend its market share and profit margins from competitors, just as a medieval moat protects a castle from invaders.

In this guide, we’ll explore the different types of economic moats, how they work, and why they matter for long-term investment strategies.

What Is an Economic Moat?

An economic moat refers to a company’s enduring competitive advantage that protects it from rivals and enables it to sustain profitability over the long term. The term captures the idea that certain businesses possess structural strengths – whether cost efficiency, brand power, or customer loyalty – that are difficult for competitors to replicate or erode.

Just as a moat defends a castle from invaders, an economic moat shields a business from competitive threats. Companies with robust economic moats often demonstrate pricing power, consistent earnings, and the ability to withstand economic cycles more effectively than their peers. These firms are typically positioned to resist margin compression, fend off new entrants, and deliver stable shareholder returns over time.

Why Economic Moats Matter in Investing

From an investment standpoint, identifying companies with durable economic moats is a powerful way to pursue long-term wealth creation. Firms with well-established moats are often industry leaders, capable of compounding earnings over years or even decades. These companies typically have the resilience to withstand competitive pressure, protect market share, and preserve pricing power through changing economic environments.

Economic moats are especially important in value investing. They not only offer protection against erosion of profitability but also reduce the risk associated with competitive threats. This makes them a key element in fundamental analysis.

Warren Buffett emphasized the importance of moats as a central part of his investment philosophy. In his 2007 shareholder letter, he stated:

“A truly great business must have an enduring ‘moat’ that protects excellent returns on invested capital. The dynamics of capitalism guarantee that competitors will repeatedly assault any business ‘castle’ that is earning high returns.”

Buffett’s point is clear: without a moat, high returns attract competition that can quickly erode those profits. But with a moat in place, a business can continue delivering superior results while fending off rivals. For investors, this translates into more predictable, sustainable performance and reduced downside risk over time.

Types of Economic Moats

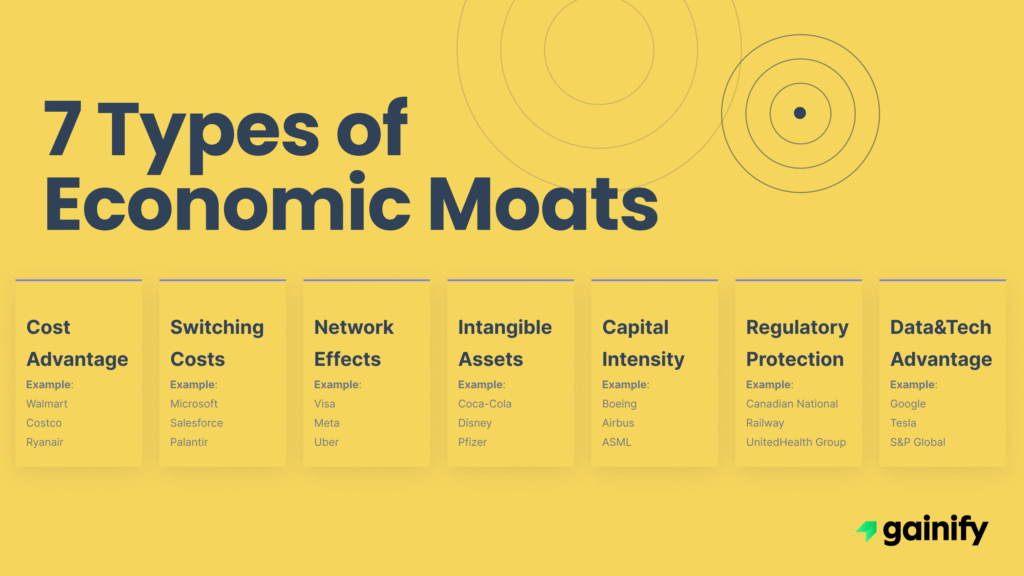

While five categories are traditionally emphasized, many analysts recognize up to seven or more types of economic moats. These moats are difficult for competitors to replicate and serve as durable defenses that allow companies to protect margins, retain customers, and extend their market leadership. Here’s an expanded breakdown:

1. Cost Advantage

A cost advantage allows a company to deliver goods or services more cheaply than its competitors, giving it flexibility in pricing and margin retention.

Examples: Walmart, Costco, Ryanair

How it works: Companies with significant economies of scale or supply chain efficiencies can offer lower prices or achieve higher profitability. This makes it hard for new entrants to compete without matching cost structures.

2. Switching Costs

Switching costs make it difficult or expensive for customers to change providers.

Examples: Microsoft, Salesforce, Palantir

How it works: Customers embedded in a platform or ecosystem may avoid switching due to time, training, integration, or financial costs. This stickiness defends market share and revenue stability.

3. Network Effects

Network effects occur when a product becomes more valuable as more people use it.

Examples: Visa, Meta, Uber

How it works: The larger the user base, the harder it is for competitors to offer a more compelling or equally scaled alternative. This creates a self-reinforcing loop of adoption and dominance.

4. Intangible Assets

These include valuable assets like brands, patents, trademarks, licenses, and proprietary technology.

Examples: Coca-Cola (brand), Disney (IP), Pfizer (patents)

How it works: Strong brands foster loyalty and premium pricing. Patents provide temporary monopolies, and licenses can restrict competition in regulated sectors.

5. Capital Intensity

A capital-intensive moat exists when the upfront costs and infrastructure requirements to enter a market are so high that they deter most potential competitors.

Examples: Boeing, Airbus, energy producers, semiconductor manufacturers

How it works: Industries like aerospace, energy, and chip fabrication demand massive investment in R&D, equipment, compliance, and distribution. This creates high barriers to entry, allowing entrenched players to maintain dominant positions and enjoy pricing power with minimal disruption from new entrants.

6. Regulatory Protection

Strict regulations can create powerful barriers that shield incumbents from new competition and limit market disruption.

Examples: Canadian National Railway, Duke Energy, UnitedHealth Group

How it works: Legal requirements, licensing, government approvals, and compliance standards make it costly and complex for new players to enter certain industries. This regulatory burden protects established firms and strengthens their market position by reducing the risk of competitive encroachment.

7. Data & Technological Advantage

Access to proprietary data, advanced algorithms, or deep technological infrastructure can create a powerful and defensible edge.

Examples: Google (search data), Tesla (autonomous driving data), S&P global (terminal ecosystem)

How it works: Companies that control unique datasets or deploy industry-leading tech platforms can offer unmatched products, predictive capabilities, or user experiences. This competitive edge grows stronger over time as data compounds and systems improve, making it increasingly difficult for rivals to replicate or catch up.

How to Identify Economic Moats

Identifying economic moats requires a blend of strategic insight, financial analysis, and industry context. While some moats may be obvious, such as a well-known brand or patent, others are more nuanced and require closer analysis.

Here are key indicators investors should consider:

- Consistent Profit Margins: Firms with wide and stable margins often enjoy pricing power or operational efficiency, signaling a sustainable moat.

- Return on Invested Capital (ROIC): A high and consistently strong ROIC suggests the company can reinvest profitably, a hallmark of durable competitive advantage.

- Market Leadership: Dominant market players with brand loyalty, scale, or customer lock-in are more likely to maintain moats.

- Customer Retention Metrics: Low churn rates, high customer lifetime value (CLTV), and strong net promoter scores (NPS) can all point to a sticky product or service.

- Financial Statement Analysis: Look for steady revenue growth, healthy cash flows, and efficient capital allocation. These factors support long-term moat durability.

Qualitative signals such as management’s ability to defend its market share, maintain pricing power, and continue innovating are equally important. Moats aren’t just about financials; they reflect a company’s long-term strategy and structural resilience.

Final Thoughts

Economic moats represent one of the most powerful concepts in long-term investing. They help identify businesses that are not only winning today but are positioned to win for years to come. While moats come in many forms—from data advantages to regulatory protection—they all share one trait: they make it difficult for competitors to erode a company’s profits.

By integrating moat analysis into your investment process, you’re not just chasing short-term returns; you’re aligning with companies that can compound value over time. Whether you’re a value investor, a growth investor, or somewhere in between, understanding and identifying economic moats is a critical edge in building resilient portfolios.